South Korea: Defense and Relation with Russia

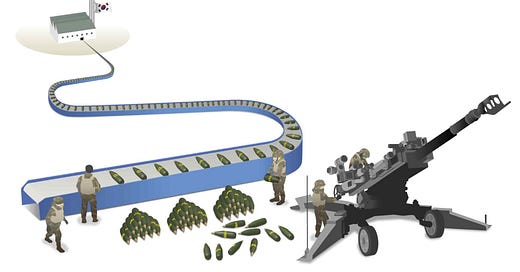

South Korea is now the world's ninth-largest arms exporter, Downturn in the bilateral relations between South Korea and Russia over the past two years

UPDATES: Already a powerhouse for technology like chips and batteries, South Korea is now the world's ninth-largest arms exporter, with the volume of its exports up 74% in the five years from 2018 to 2022. In 2022, Yoon announced his goal of taking the world's fourth spot by 2027.

Seoul and Moscow have seen a sharp decline in their bilateral relations ov…