Munich Security Conference and Report

Blinken, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to meet Friday at Munich Security Conference, U.S. political uncertainty looms over key security conference in Munich, Migration more critical than Russia

UPDATES: Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi are likely to discuss planning for a phone call this spring between President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Speaking at the Munich Security Conference on Friday, Vice President Harris will try to allay concerns among European allies about American resolve in major conflicts across the globe while also aiming a message to voters at home: electing Donald Trump in November would destabilize the global order.

Germans now view issues like migration and the threat from radical Islam as more immediate concerns than the menace in the Kremlin. That’s according to new research published Monday ahead of the Munich Security Conference.

Antony Blinken's (right) upcoming meeting with Wang Yi (left) underscores Washington and Beijing's efforts to cool the rancor that has roiled U.S.-China ties over the past year. | Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images

Blinken, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to meet Friday at Munich Security Conference

By PHELIM KINE, POLITICO

Secretary of State Antony Blinken will meet with China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference on Friday, two sources familiar with the planning tell POLITICO.

Blinken’s one-on-one meeting with Wang in Washington last October helped pave the way for President Joe Biden’s November summit with China’s leader Xi Jinping in California.

Last month, Wang met in Bangkok with national security adviser Jake Sullivan.

China’s Foreign Ministry announcement that Wang would attend the conference made no mention of a meeting with Blinken. The State Department announcement of Blinken’s Munich agenda said his focus would be Ukraine, the Middle East and “transatlantic security.” Neither the State Department nor the Chinese embassy in Washington responded to requests for comment.

The Blinken-Wang meeting agenda in Munich will likely include planning for a phone call between Biden and Xi in the coming months. A senior administration official’s readout of Sullivan’s meeting with Wang in January mentioned that such a call would occur sometime “this spring,” without elaborating.

Blinken’s upcoming meeting with Wang underscores Washington and Beijing’s efforts to cool the rancor that has roiled U.S.-China ties over the past year. Bilateral relations nosedived following the discovery — and subsequent destruction by U.S. Air Force fighter jets — of a Chinese spy balloon over the continental United States in February 2023.

Both sides have emphasized the need to maintain open lines of communication to prevent a relationship sorely strained by Chinese intimidation toward Taiwan, rising tensions between Manila and Beijing in the South China Sea and Xi’s “ no limits” partnership with Russian President Vladimir Putin from veering into potential conflict.

The White House considers its nine months of focused engagement with Beijing a diplomatic success. In recent weeks Biden administration officials have repeatedly touted how that outreach has resulted in the creation of a U.S.-China Counternarcotics Working Group, the resumption of bilateral military-to-military contacts and an agreement to discuss safe development of artificial intelligence.

Read here.

Bavarian State Gov. Markus Soeder welcomes Vice President Harris with a gingerbread heart upon her arrival Thursday for the Munich Security Conference. (Matthias Schrader/AP)

U.S. political uncertainty looms over key security conference in Munich

By Cleve R. Wootson Jr., Emily Rauhala, Michael Birnbaum and Souad Mekhennet

Speaking at the Munich Security Conference on Friday, Vice President Harris will try to allay concerns among European allies about American resolve in major conflicts across the globe while also aiming a message to voters at home: electing Donald Trump in November would destabilize the global order.

Harris’s speech — which will mark her third appearance at the annual confab of world leaders and policy and security officials — precedes a busy weekend in which she will meet several European leaders, including German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Speaking just days after Trump set off new anxiety by saying he would encourage Russia to attack NATO partners that underspend on defense, Harris may find it difficult to reassure Washington’s transatlantic partners, who are keenly aware of the electoral uncertainty of this year’s presidential contest.

In a background briefing to reporters, a senior administration official said Harris will argue that isolationism and support for authoritarian governments only weakens the United States and hurts its people.

It is in many ways a global spin on Biden and Harris’s reelection message that Trump would undo the progress the administration has made over the past three years in rebuilding trust in Washington.

Harris “will make a forceful case for the Biden-Harris Administration’s worldview and continued global leadership,” the senior administration official said, and will denounce Trump’s foreign policy framework “as shortsighted, dangerous, and destabilizing.”

“She will argue that they could lead to a world of disorder — to the detriment of the American people and the world,” the official added.

There is, of course, much to discuss at this weekend’s gathering in Munich: worrying reports of Russian advances from the front lines of eastern Ukraine; Israel’s plans for a potentially devastating ground assault on Rafah; and an unspecified “space threat” from Russia, for starters.

Yet one question seems to hang over this year’s Munich Security Conference: What, exactly, is happening in the United States?

For months now, Europe’s political, security and intelligence establishment has watched nervously as critical Ukraine aid became mired in domestic politics. American interlocutors assured the Europeans that, ultimately, the bill would pass and money and military equipment would continue to flow.

But the protracted fight over the funding, combined with former president Trump’s claim that he would encourage Russia to attack U.S. allies for meager defense spending, has jolted Europe, renewing doubts about whether the continent can count on the United States — and what to do if it can’t.

In public remarks and private conversations over the next two days, Harris will try to combat that skepticism from allies deeply unsure if she will even be vice president a year from now.

As the race for the White House barrels toward a two-person contest, President Biden has struggled in some polls against Trump. Questions about Biden’s age and mental fitness continue to be a drag on his favorability ratings.

Harris’s advisers hope a strong performance on the world stage will help blunt questions about her ability to perform in the nation’s top job — an important requirement for the understudy to the oldest president in U.S. history.

For Harris, who is widely expected to seek the White House herself at some point, the trip to Germany is also an opportunity to cement her foreign policy bona fides, and to strengthen relationships with allies.

In Munich, Harris and Secretary of State Antony Blinken will try to convince European allies that the U.S. commitment to Ukraine and NATO remains steadfast. But there appear to be few promises they can make about the next few months, let alone the next years.

They will be joined in Germany by Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, who is fresh off an unprecedented impeachment that has made him a symbol of U.S. political dysfunction to some here. A group of U.S. senators flying over for the event, meanwhile, will face questions about why Republicans seem to be “owning” Trump’s message about abandoning Ukraine.

Some of those questions could come from Zelensky, who will swing by Munich after stops in Berlin and Paris on Friday. Those trips are aimed at shoring up longer-term support for Ukraine’s fight — and signaling European resolve.

Europe, for its part, will be doing its best to show U.S. officials — and a certain presidential candidate — that they are holding up their side of the transatlantic bargain.

In Brussels this week, for instance, senior officials, including NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, played up recent increases in defense spending by NATO members.

In remarks to the press, Stoltenberg insisted that critics such as Trump have a “valid point” when it comes to defense spending, but that the alliance is already moving toward spending more.

“It’s a point and a message that has been conveyed by successive U.S. administrations that European allies and Canada have to spend more, because we haven’t seen fair burden-sharing in the alliance,” Stoltenberg said. “The good news is that this is exactly what NATO allies are now doing.”

NATO saw an 11 percent real increase in defense spending across Europe and Canada last year. This year, 18 of 31 allies will meet the target of spending 2 percent of their GDP on defense, Stoltenberg said.

European leaders recognize the limits of their influence in the U.S. political debate, although many of them are trying to push the conversation anyway.

In recent months, a stream of foreign and defense ministers and senior European officials have undertaken visits to Washington that follow a predictable itinerary. Meetings with administration officials plus whichever congressional Republican lawmakers are amenable. Then they do an event at a conservative think tank, such as the Heritage Foundation or the American Enterprise Institute, trying hard to sway the opinions of the surging isolationist wing of the Republican Party and to bolster the party’s faltering foreign policy hawks.

Many E.U. diplomats hold out hope that the United States will come around, in part because they don’t wish to ponder the alternative. “We believe that the defeat of Russia in Ukraine is a common interest,” said a senior E.U. diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity to brief the media.

“From what we understand from our U.S. colleagues, there is still possibility that Congress approves,” the diplomat continued. “We hope so — their support will remain much needed over the next months and years.”

Read here.

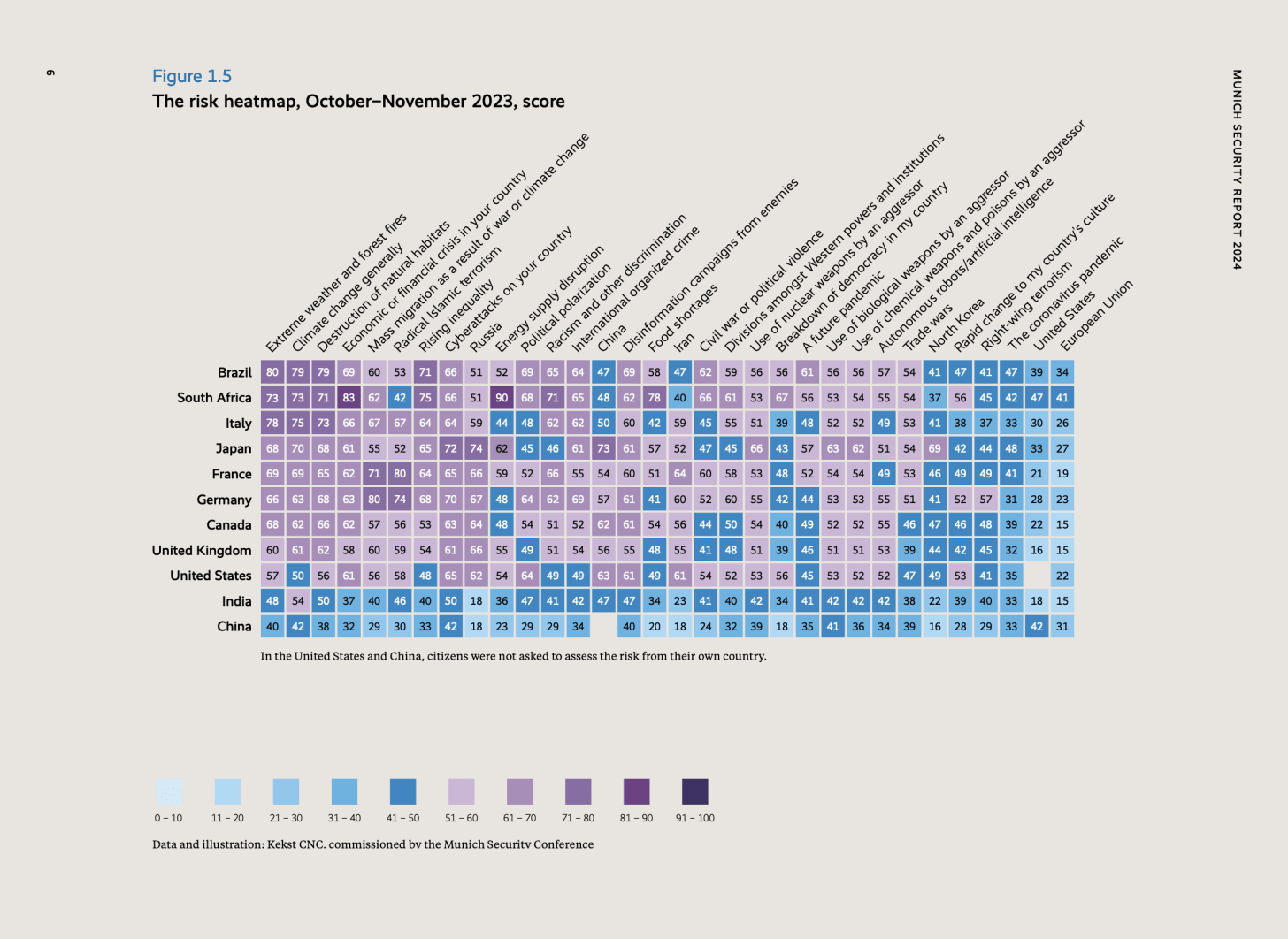

Taken from the Munich Security Index 2024

Russia no longer perceived as top threat by Germans

Russia is showing no signs it plans to wind down its unprovoked assault on Ukraine two years after launching a full-scale invasion — but Germans now view issues like migration and the threat from radical Islam as more immediate concerns than the menace in the Kremlin.

That’s according to new research published Monday ahead of the Munich Security Conference, a gathering of top political and defense officials which kicks off in Germany on Friday.

While Russia was perceived as the number one threat in Germany in last year’s Munich Security Index, it has now slipped back to seventh place in the annual report.

The pattern is replicated across the G7 group of countries — the threat posed by Russia was cited as the top concern in surveys conducted in late 2022 for the 2023 Munich Security Index, but has dropped to fourth overall a year later.

The findings come at a crucial moment in the war, as Ukraine seeks to shore up European support as the United States’ commitment to the war effort falters due to continuing Republican opposition in the U.S. Congress.

The European Union agreed a €50 billion aid package for Kyiv earlier this month, but there's already evidence it’s insufficient as Ukraine’s financial needs grow by the day.

The survey’s conclusion that the German public is less concerned by the Russian threat than it once was is a sign of the shifting priorities in Europe as the intractable war enters its third year.

While Ukraine has inflicted significant damage on the Russian army since the war began, its 2023 counteroffensive made slow progress. In a bid to reset his country’s military strategy, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy replaced his top general Valery Zaluzhny last week with Oleksandr Syrskyi, and embarked on a wider leadership reshuffle.

The war in Ukraine is expected to dominate this year’s Munich Security Conference. Though it has not been confirmed, Zelenskyy himself is widely expected to make an appearance — two years after he flew to Munich to make a desperate plea for international help at the conference just days before Russia's full-scale invasion began.

The Munich Security Index 2024 also reveals how the war in Ukraine is competing with other geopolitical threats and priorities.

Concern about mass migration and radical Islamic terrorism now top the list of threats in Germany — a turnaround from the previous year.

The threat posed by radical Islamic terrorism jumped to second place, compared to 16th last year. Mass migration as a result of war or climate change, which came in second last year, now ranks sits at number one. The authors of the report attribute the trends to the Hamas attacks on Israel on October 7, noting the survey was undertaken in October and November last year.

“As in many other countries, the Hamas terrorist attack on October 7 appears to have prompted a spike in German concern about radical Islamic terrorism,” the report notes, adding that “Germany now has the highest level of concern about migration among the countries surveyed.”

Read more