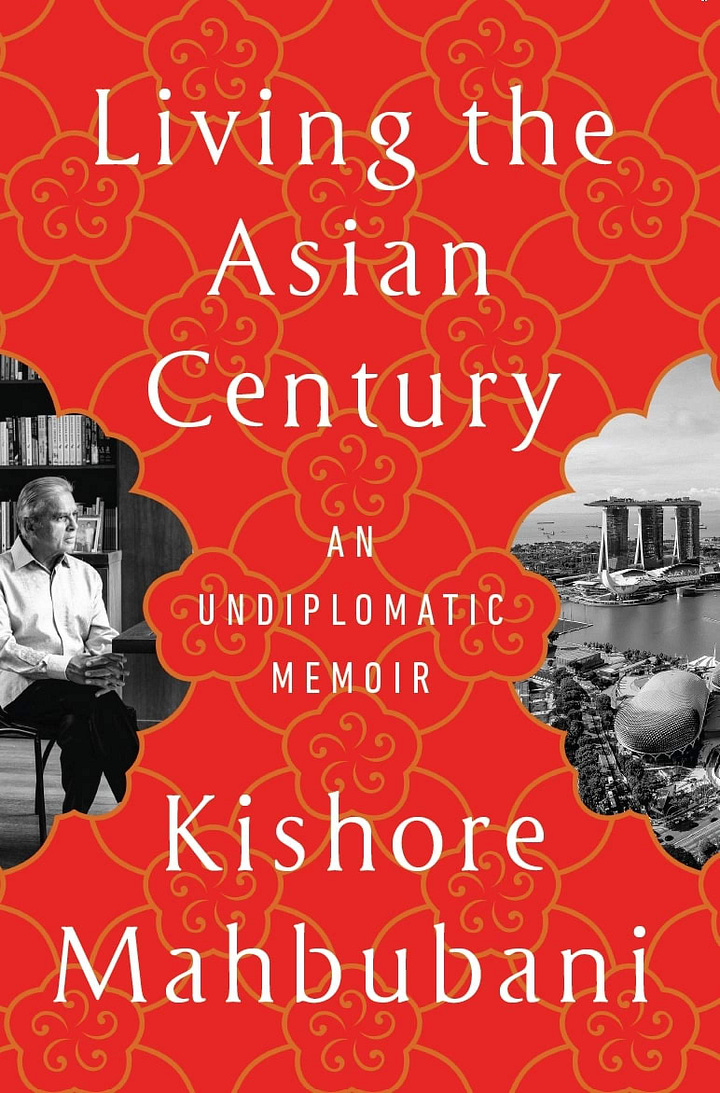

Kishore Mahbubani

Imagine the poetic justice if the UK were to cede its UNSC seat in favour of India, Nuclear submarine detection, deterrence, destruction.

UN credibility depends on adjusting veto rights to match shift in global power

Imagine the poetic justice if the UK were to cede its UNSC seat in favour of India

The writer, a distinguished fellow at the National University of Singapore, is the author of ‘The Asian 21st Century’

Fifteen years have passed since Martin Wolf wrote, “Within a decade a world in…