Intersections

UPDATE: The mass hysteria reflects the biases inherent in the world’s most powerful media outlets. A key feature of mainstream Western media today is the relentless China-bashing. It is off the charts and tiring, often involving regurgitated trivia or fabricated stories with no evidence to support callous statements about the country, demonstrating a deep lack of understanding. But such stories continue to be churned out with no end in sight.

The 18th G20 summit in New Delhi couldn’t make any tangible progress on key goals, but they did agree on a joint declaration given the stark divergences of the summiteers on the Ukraine war – something that scuppered the 2022 summit in Bali, Indonesia.

Since Prime Minister Hun Manet was appointed as the country’s new leader, US Ambassador to Cambodia Patrick Murphy has been actively holding meetings with important figures in Cambodia. He has also had two meetings with Hun Manet, the country’s current leader who attended school in the US.

Anti-China Rhetoric in Western Media

By Chandran Nair

The mass hysteria reflects the biases inherent in the world’s most powerful media outlets. A key feature of mainstream Western media today is the relentless China-bashing. It is off the charts and tiring, often involving regurgitated trivia or fabricated stories with no evidence to support callous statements about the country, demonstrating a deep lack of understanding. But such stories continue to be churned out with no end in sight.

Countering this in international media by offering more balanced views for a global audience is near impossible as censorship is rife. There almost seems to be a global compact to control the narrative, a propaganda war powered by today’s digital technology.

Just try looking for a positive story on China any day of the week in any of the leading global media outlets. Apart from reports in January about the Lunar New Year, there will hardly be any, and these too are likely to have a negative spin. It would appear there is a confidential memo circulating within Western media groups that guides reporters and editors to ensure there cannot be any positive news arising from a country with 1.3 billion people.

Typically, the negative stories adhere to three core ideas, which inform the unspoken guidelines within these press rooms when it comes to reporting on China.

First is the belief that China is a threat to the world and that this belief must be relentlessly reinforced at every available opportunity. How and why China is a threat is never explored; such is the deep-rooted and almost religious nature of the belief. Sound arguments do not matter. The basic tenets of good journalism are ignored when it comes to a China story. There is no need to explain or give evidence of why China is a global threat.

Left ignored is the plentiful evidence that shows China is not a global threat – even if one can point to mistakes and overreach in certain areas. China has not invaded any country in decades, or imposed sanctions that have devasted the lives of millions in poor countries, unlike the West, led by the United States.

Second is that China must be linked to every possible global event that affects the West. This provides an opportunity for the West to bash China while simultaneously burnishing its own credentials as the supposed arbiters of what is right and wrong in international relations. From the pandemic to the Russia-Ukraine war to carbon emissions; from rising sea levels to the scramble for rare earths; from the building of infrastructure in Africa to the production of vaccines – there must be an angle to demonize the country and instill fear in Western nations (and beyond).

Indeed, media outlets are reverting to the “yellow peril” of the late 1800s. There is no subtle and nuanced approach to instilling fear like this. It is full-on and very often blatantly racist – but it is now acceptable for one to be racist about the Chinese in Western media, despite the fact that Black-White relations are very carefully described.

The third part of this phenomenon, which is surprisingly not challenged by liberal readers of mainstream media, is the sentiment that everything must be done – even illegal and unfair methods – to arrest the rise of China. Never mind the rights of hundreds of millions of Chinese to have a better life after a century of poverty and deprivation.

Headline after headline that capture this sentiment have normalized the view that there is a need to curb the rise of China, and that this is a legitimate geopolitical objective. There is no explanation about why or if it is even morally acceptable. It has become a feature of Western commentary on China to say that its rise is a concern and a threat. With this assumption unassailably in place, the West has the right to galvanize – and even bully – its allies and ask the absurd question, “what should be done about China’s rise?” – as if China does not have the right to carve its own place in the new world.

There is even a school of thought in the United States that it was America that magnanimously allowed China its first baby steps into the globalized economy, and that in hindsight the U.S. was too nice to China. This view betrays everything that is imperial about the West and why it is unable to come to terms with the legitimate rights of other nations to grow and become powers in their own right. The assumption is that the rise of others is a gift from the West, and accordingly they must never challenge its supremacy. The deeply entrenched view in the West from centuries of domination is that it will decide which nations will be permitted to be participants in the global economy according to its self-serving “rules-based order.”

Indeed, Western media seem wholly tied to the hegemonic competition view of geopolitics, constantly referencing the “Thucydides Trap” and being stuck in the Western canon as if there are no other ways of looking at geopolitics and world order. This view assumes conflict is inevitable and helps to demonize China while justifying the hegemonic position of the West – and the United States in particular – as a globally stabilizing force.

Needless to say, this is an extremely belligerent position to take, and not something media should be egging on. Whatever happened to promoting multilateralism? And why are people who speak to multilateralism side-lined as idealists or China apologists? This flies in the face of fair reporting.

So, how to fix this?

First, people in China and the non-Western world must realize that when it comes to the workings of the mainstream media we are in a new era – a propaganda war the likes of which the world has never seen before, powered by today’s digital technology. The media war is real, and tech-driven, and it is not a fight for eyeballs to deliver fair, honest, and educational news. It is almost everything else but that, especially when it comes to China or enemies of the West.

On one side is sheer propaganda aimed at the preservation of Western power. Participants include the most well-known brands in the Western media world, which are household names across the world.

The idea that Western media is run by fair-minded people who are independent, driven only by a desire to talk truth to power, is a mirage. It is a myth, and it is a bitter pill that needs to be swallowed. The idea that the Western journalist is a paragon of virtue also needs to be banished from the minds of consumers of media.

That is the first stage in enabling one to step out of the propaganda mist we are engulfed in on a daily basis, so that one can examine different viewpoints as news is consumed. This is not easy, given the current dominance of Western media outlets and their apparently collective mission.

The next step is to dismantle the dominance of Western media.

This too will be a long, hard fight. Mainstream Western media are the most powerful in the world and for close to a century, Western media have had a stranglehold on the dissemination of international news and viewpoints across the world. Many had their origins in colonialism, the preservation of empire and later the spread of Western ideas about how the world should be run. These outlets are a powerful economic force and dislodging them will require investments.

Across the world there is an opportunity to contribute to this effort, not necessarily by building large media companies but by investing in media companies that are committed to fair and objective analysis, so that local audiences in the first instance have choices and are not inundated by the propaganda of mainstream Western media. This too will not be an easy task and there are many hurdles to overcome, but this is not the space to dive into those details. Ultimately, it is all about readers becoming more aware of global issues by having more non-Western sources to rely on, so they are not victims of the current propaganda war. This is beginning to happen as more alternatives flourish.

It is an urgent need in the West too so that the mass hysteria generated by mainstream media is prevented from creating fear and pitting Western societies against the rest of the world. Today the target is China; tomorrow India and then maybe Africa.

Read more here.

Corridor wars

By Naveed Hussain

The 18th G20 summit in New Delhi was a big win for India’s diplomacy. Or, it was touted as one. The leaders of the 20 major economies couldn’t make any tangible progress on key goals of the bloc, but they did produce a formal communiqué that garnered unanimous support from all participants. It was a complete surprise because it looked next to impossible a few days before the summit that the bloc could agree on a joint declaration given the stark divergences of the summiteers on the Ukraine war – something that scuppered the 2022 summit in Bali, Indonesia.

A careful reading of the Delhi communiqué shows that the Western nations made a compromise to ensure India scores this “diplomatic victory”. They acquiesced to a diluted language in reference to the Ukraine war. The declaration neither names nor condemns Russia over the conflict in which they have pumped tens of billions of dollars. Instead, it only talks about “the human suffering and negative added impacts of the war in Ukraine with regard to global food and energy security”. It was a climbdown by the Western nations because the Bali summit failed due to their insistence that the participants unanimously “deplored in the strongest terms the aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine and demanded its complete and unconditional withdrawal from the territory of Ukraine”.

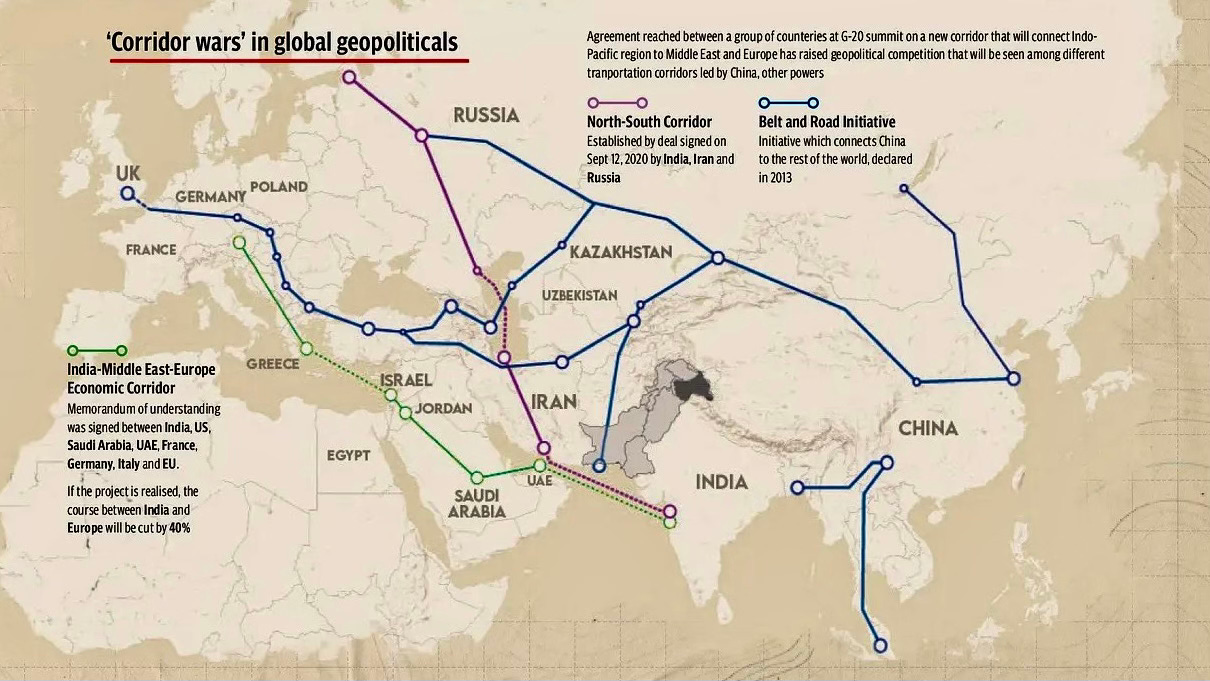

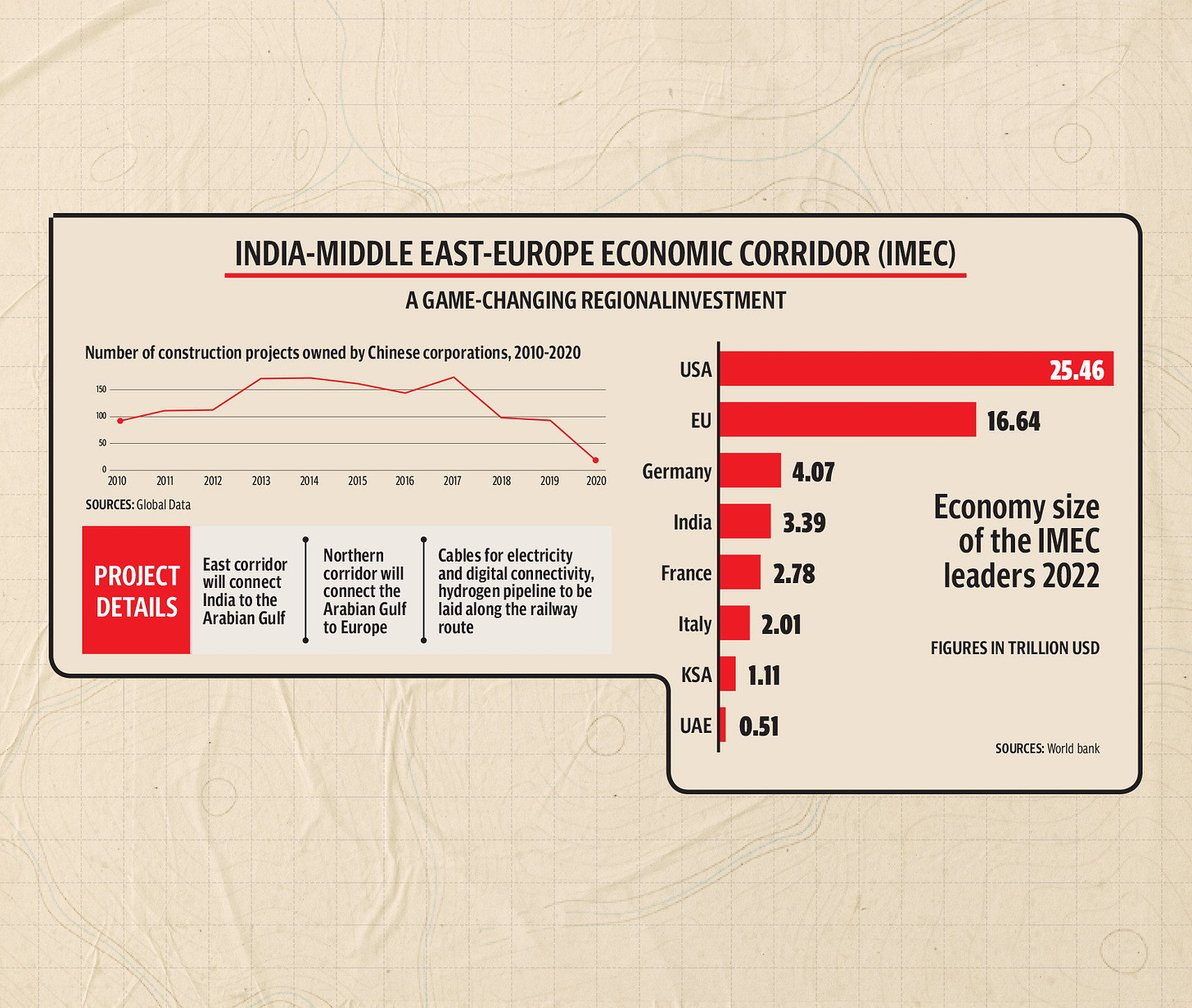

But why would the US and its allies back down on something they have thrown in their lot with? While analysts were trying to figure out, President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Narendra Modi sprang up the answer. Together with Saudi and Emirati royals, they announced the launch of India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a multibillion-dollar infrastructure and investment project that would “enhance movement of trade and services to transit to, from, and between India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, and Europe.” It would also provide India secure connectivity and upgrade ties with Arab states as Delhi’s dependence on the Middle Eastern energy industry grows. The IMEC turned out to be the biggest takeaway from the G20 summit.

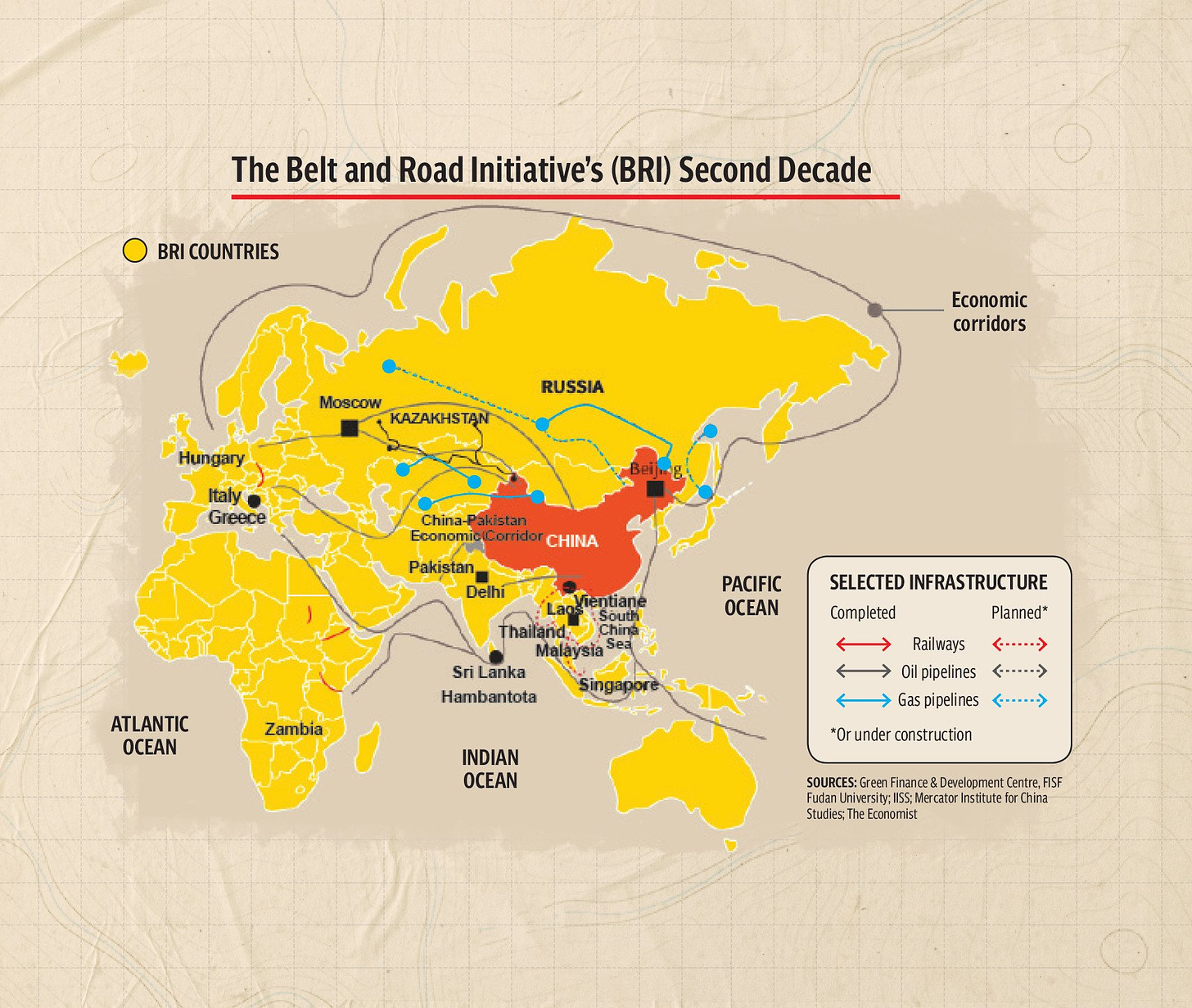

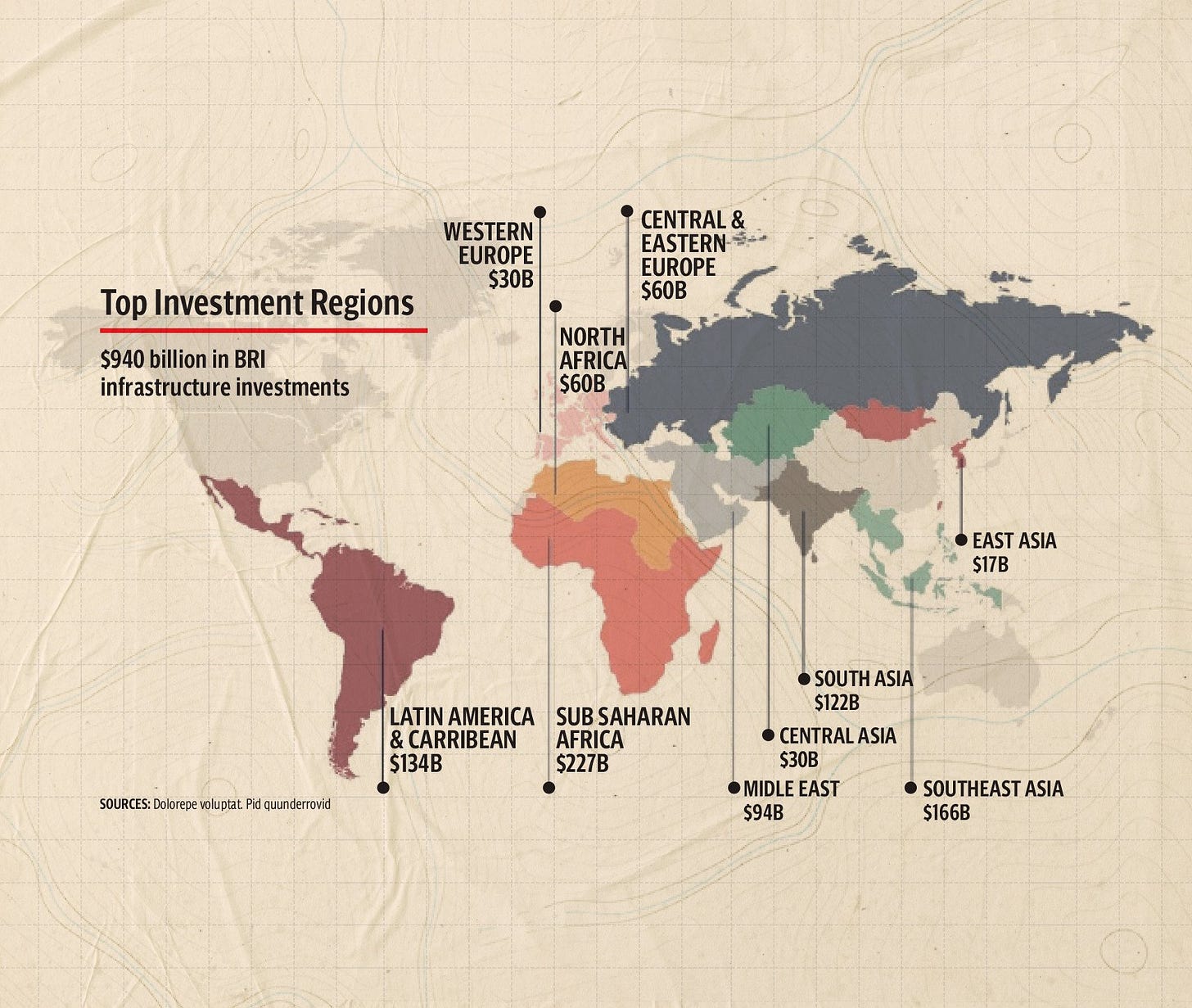

If the IMEC is all about expansion of India’s geoeconomic outreach, then why would the US and its allies cheer it as a “game-changing regional investment”? Because they have been projecting India as a counterweight to China which, they believe, is trying to threaten their “rules-based world order”. The IMEC appears to be a Western response to China’s gigantic Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that seeks to reimagine the fabled Silk Route to connect China to Central, South, and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. However, it defies logic that the $17billion IMEC could rival the $1 trillion BRI, which has become the world’s largest-ever global infrastructure project involving nearly 150 countries.

The BRI is the embodiment of China’s concept of a “human community with a shared future”. But the Western policymakers fear “China could convert its economic outreach into political sway, pressuring countries not to take stances that run counter to China’s interests on sensitive issues. China’s investments in overseas ports would give its military greater power projection capabilities”. Spurred by this fear the US continues to undermine the BRI in a sustained effort to safeguard its global hegemony. And interestingly it makes no secret of its intent. The US managed to make some countries change their mind. Israel buckled under US pressure and backed off from allowing a Chinese company to run its Haifa port. Italy has also hinted at possible exit from BRI. Greece, however, has defied pressures over the Piraeus port deal with China’s Coscos maritime giant even though the US clearly warned Rome against becoming the “head of dragon”.

India is just a pawn. The IMEC’s real beneficiary will be the US. The project’s primary objective appears to be America’s attempt to undercut China by projecting India as the leader of the Global South. Secondly, the US might also be trying to wane Delhi away from the North-South Transport Corridor which would ultimately benefit Russia and Iran. Thirdly, the US could also be using the IMEC to reassert its weakening role in the Middle East where China has made successful inroads. Recently, Beijing scored a massive geopolitical feat by brokering a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran and between the Arab League and Syria. Now, the US is using the IMEC to offset the Chinese move by negotiating peace between Riyadh and Tel Aviv in an attempt to again isolate Tehran.

Traditionally, the US has been the guarantor of security for the Gulf nations. But Saudi Arabia and the UAE became disillusioned with the US and started cozying up to China following President Donald Trump’s disengagement policy. Now, they have been invited to join BRICS, an economic bloc that the US fears could challenge its liberal world order. Saudi Arabia and the UAE might have agreed to become part of the IMEC mainly to balance their ties with both the US and China. Their decision might have been dictated by geopolitical compulsions, but a long-term commitment to an overtly counter-China project may not fit into their new foreign policy paradigms. Moreover, hostility with Iran undermines Saudi de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 that aims to position the kingdom as a global logistics and tourism hub. The recent Saudi peace overtures towards Iran, Yemen, and Syria are seen in the same context.

Iran and Turkey have been left out of the IMEC which makes the geopolitical imperatives of this US-helmed project even clearer. Angered by the snub, President Reccep Tayyib Erdogan openly opposed the project, saying “there could be no corridor without Turkey.” Instead, he proposed expediting the $17 billion Iraq Development Road Project because Turkish experts doubt the stated primary goal of the IMEC as they believe it is purely driven by geostrategic concerns.

Iran hasn’t publicly commented on the new connectivity initiative. However, Tehran might not be happy with India embracing the US-led corridor while dragging its feet on the Chabahar port which is a key link in the INSTC that aims to link India to Europe through Iran, Azerbaijan and Russia. Iran may also be opposed to the IMEC due to its counter-BRI undertones. Tehran has developed solid relationship with China especially since 2021 when Beijing agreed to invest $400 billion in the Islamic Republic in exchange for supply of oil under an economic and security agreement.

Since the end of Cold War, the US has been cobbling up alliances of likeminded nations for geopolitical objectives. India is a part of or at least supportive of these alliances, especially of the ones coalesced to challenge China in the Indo-Pacific region. India is a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD), commonly known as Quad, a strategic security dialogue between Australia, India, Japan and the United States. Quad, dubbed “Asian NATO” by Chinese security experts, is propelled by the overlapping interests of its members to deter Beijing from challenging the status quo in South China Sea. Similarly, India has also been invited to join AUKUS, a trilateral military alliance of Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States against China. Though India has thus far resisted the urge to join AUKUS, but it has fully supported the alliance against criticism from China and Russia because it knows that this coalition could offer Delhi the leeway to engage with China from a position of strength.

For these reasons, India was the obvious Western choice to lead a counter-BRI project in this region. However, it’s not the first such attempt by the United States. In 2011, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton unveiled the “New Silk Road Initiative”, the brainchild of CENTCOM chief General David Petraeus that sought to integrate Afghanistan further into the region by reviving traditional trading routes. The project never got off the ground. Then in 2021, President Biden, together with his G7 partners, announced the launch of Build Back Better World (B3W)”. B3W, “a values-driven, high-standard, and transparent infrastructure partnership led by major democracies to help narrow the $40-plus trillion infrastructure need in the developing world”. Behind this grandstanding hid the G7’s real intent of offsetting China’s growing economic and cultural influence. The project was described with all lofty adjectives in dictionary, but it too failed to move forward because the US and its G7 allies got bogged down in the Ukraine war which has become a black hole for Western money.

The same year, the European Union unfurled an ambitious €300 billion “Global Gateway”, which envisaged modern infrastructure projects outside the EU as a “true alternative” to BRI. But nothing has been heard about it since. A year later, the G7 unveiled the ‘Program for Growth in Infrastructure and Investment (PGII)’, which, according to the White House Factsheet, aims “to mobilise hundreds of billions of dollars and deliver quality, sustainable infrastructure that makes a difference in people’s lives around the world, strengthens and diversifies our supply chains.” The IMEC, together with a Trans-African Corridor, has been launched under this same PGII initiative. EU President Ursula Gertrud von der Leyen, while speaking at an event on the sidelines of the Delhi G20 summit, hailed the development as “nothing less than historic”.

The IMEC is in its embryonic stage. Only a memorandum of understanding has been signed and none of the partners has made any financial commitment thus far. The signatories are scheduled to meet again next month to announce an action plan, though none of them is obligated to take action towards its implementation. India’s embrace of the corridor is driven by its overambitious geopolitical objectives and geoeconomic interest, but Delhi has neither resources nor expertise to undertake such a gigantic infrastructure development undertaking. Furthermore, the ongoing tensions between India and Canada over the murder of a Sikh separatist leader, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, may also dampen the prospects of any meaningful progress at the next month’s meeting of the IMEC signatories.

Conflicting geoeconomic interests of key regional players aside, the IMEC’s fate may not be different from the previous such initiatives because it is primarily driven by the strategic imperative to counter China using bloc politics rather than by a true desire for synergising cooperation for “economic development through enhanced connectivity and economic integration” to make a difference in the lives of people.

Read more here.

Strengthening US-Cambodia Ties

By Dr. Seun Sam

Since Prime Minister Hun Manet was appointed as the country’s new leader, US Ambassador to Cambodia Patrick Murphy has been actively holding meetings with important figures in Cambodia. He has also had two meetings with Hun Manet, the country’s current leader who attended school in the US.

It would be reasonable to assume that both Cambodia and the US desire to have excellent ties. Ambassador Murphy really hopes to build a cordial relationship between the two countries. Why is it so difficult for me (Cambodia) to simply be a friend of the US, Hun Sen asked when he visited the US in 2022.

What are the issues and difficulties in establishing positive ties between Cambodia and the US?

First and foremost, we must admit that the US was one of the first nations to establish diplomatic ties with Cambodia before any other nations in the area or the entire world, and that the US actively encouraged Cambodia to secede from France. The largest market for Cambodia to export its goods at the moment is the US market, which is highly significant for Cambodia. However, there are also other factors that need be taken into account, thus those two primary elements are insufficient for the countries to build positive relationships with one another.

It is essential to have a thorough understanding of the relationship between the two countries in order to successfully repair bilateral relations between the United States and Cambodia.

Relationships between the US and Cambodia have been tense recently for a number of reasons. Former Prime Minister Hun Sen’s administration in Cambodia has come under fire for perceived repression of political dissent, limitations on the right to free speech, and alleged abuses of human rights. US authorities have expressed worry over these steps, which have also strained diplomatic ties between the two nations.

In addition, in response to these worries, the United States has imposed sanctions on specific Cambodian officials and businesses. These restrictions have made the relationship even more complicated and made it difficult for diplomatic efforts to succeed.

It is crucial to keep in mind that the United States and Cambodia do have some areas of collaboration and common ground. The two nations have a history of working together on problems like anti-terrorism, local security, and economic growth. Building bridges and sustaining a positive relationship will depend on recognizing these shared objectives and potential areas of cooperation.

The US Ambassador and Cambodian Prime Minister must conduct an exhaustive examination of the current situation of US-Cambodia relations in order to effectively rebuild bilateral relations.

This entails looking at the underlying reasons why the relationship is tense, comprehending the worries and interests of each party, and finding possible areas of agreement.

In order to learn more about political attitude, policy initiatives, and important areas of attention, the US Ambassador and Cambodian authorities should commit time and resources to this task.

This could entail speaking with local stakeholders, journalists, and specialists knowledgeable about Cambodian politics, as well as examining public speeches, official pronouncements, and policy documents.

Open and regular communication is one of the most crucial strategies to build rapport and trust. This entails opening diplomatic channels of communication and keeping in touch frequently. Both parties can lay the groundwork for trust and understanding by showing a sincere interest in one another’s worries and goals.

Showing respect for one another’s cultures and customs is also crucial. Both sides can show that they genuinely want to cross the cultural divide and promote respect for one another by becoming familiar with and embracing the local traditions. This can be accomplished through participating actively in campaigns that encourage cross-cultural exchange, attending significant cultural events, and interacting with local community leaders.

Building bridges and repairing mutual relations between the US and Cambodia need addressing human rights concerns and advancing democratic values. Regarding the deterioration of democratic values and breaches of human rights, Cambodia has recently come under attention and criticism. It is not important for Cambodia to repress those who work for NGOs and environmental activists, Cambodian government should support those people in order to gain good reputation in the world.

When it comes to bridging gaps and mending fences between nations, diplomacy’s importance cannot be overstated. The relationship between the US ambassador and the prime minister of Cambodia serves as a prime example of the value of diplomatic efforts in settling disputes, clearing up miscommunications, and fostering understanding.

A vital technique for fostering communication, encouraging cooperation, and identifying areas of agreement between countries with potentially divergent interests or viewpoints is diplomacy. It enables genuine dialogue, compromise, and negotiation—all of which are crucial for mending strained bonds.

The US and Cambodia must establish open lines of communication, look for chances for dialogue, and show a sincere interest in comprehending and addressing the issues and objectives of the host country if they truly want to build positive relations.

Diplomatic efforts shouldn’t be restricted to official negotiations and high-level gatherings. Cultural gatherings, educational initiatives, and people-to-people contacts can all significantly contribute to international understanding and bridge building.

Diplomatic efforts ultimately depend on endurance, perseverance, and a dedication to finding common ground. It necessitates the capacity to maneuver through complex political environments, adjust to shifting conditions, and give priority to long-term objectives over immediate rewards. While rebuilding international ties is a difficult work, with the correct diplomatic strategy, it is possible to close gaps, promote cooperation, and open the door for a more peaceful and fruitful partnership.

Read more here.