Diplomate et Diplomatie

Le marquis de Custine, Poutine et la Russie éternelle, Cooperation between the UN, CSTO, CIS, and SCO, Fighting for the independence of France's overseas territories.

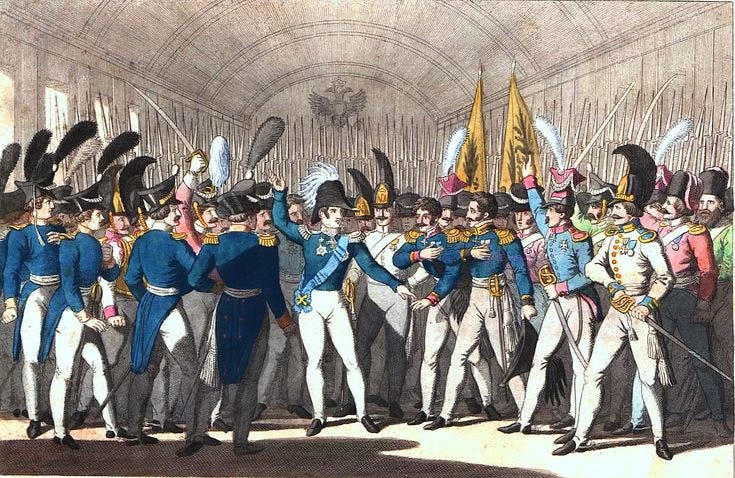

Le marquis de Custine, Poutine et la Russie éternelle

By Guillaume Lagane (The Conversation France)

On le sait depuis le succès de ses Lettres…